Shall we look at the exciting topic of SPELLING?

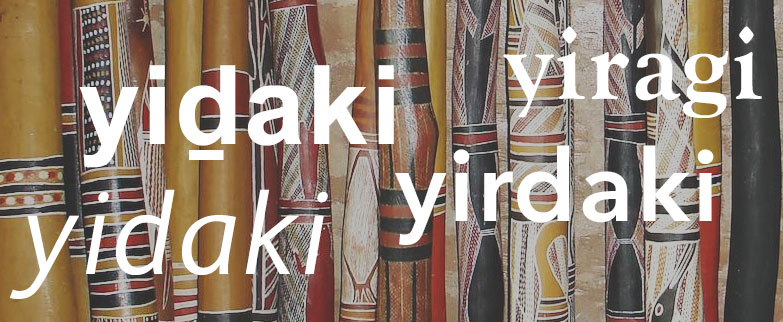

Have you ever wondered why are there so many different spellings of the main Yolŋu word for “didgeridoo?” Or should that be “didjeridu?” “Didgeridu?” “Didjeridoo?” And now we’re off the rails already.

Get back to the point. That’s not even the word we’re talking about.

OK. The reason it’s hard to standardize the spelling of the Yolŋu word is simple. It’s not an English word. It contains one particular sound that we do not make in English – the retroflexed [d].

To produce the sound, touch the tip of your tongue to the back of the alveolar ridge – that bump behind your top teeth – and then say a [d]. Don’t push way back to the roof of your mouth. Just touch the edge of that ridge. When you say a “normal” [d], the tip of your tongue touches just behind the teeth. For the Yolŋu retroflexed [d], you move the tip of the tongue back about a centimeter. For North American English-speakers like me, Spanish-speakers, 18th century pirates, and many others, your tongue is curled back the same amount as to say the letter [r], but you move the tip of your tongue straight up until you touch the ridge to make it a modified [d] instead. That’s it. Yolŋu do the same with the letters [l], [n] and [t].

Since we don’t make that sound in our languages, we don’t have a way to write it. When we just write “yidaki,” we’re ignoring the issue and letting readers think of the [d] they know. Which, honestly, is fine most of the time. “Yiḏaki” and “yirdaki” use [ḏ] and [rd] as code to indicate the retroflexed position, but they only work for readers who know the code. Let’s look at that.

Yidaki

Since Beulah Lowe’s pioneering work to document Yolŋu languages at Milingimbi mission in the 1950s, underlining the consonant [d], [l], [n] or [t] has been the standard way to write retroflexed letters in these languages. It’s what all the Yolŋu I know do. It’s in their educational materials and on signs around town. To me, this is the best way. As I said, it just doesn’t mean anything to you until you know the code. Now you know.

Yirdaki

Some academics have used the [rd], [rl], [rn], [rt] convention to indicate the retroflexed tongue in Aboriginal languages. Once again, it is a code that works for readers who know the code. It makes sense because, as we’ve seen, the retroflexed [d] uses a curled tongue like an [r], but you touch the gum ridge to make a harder consonant. Moving into that position from a vowel sounds ALMOST like you’re saying an [r] first. Yolŋu languages never use a separate “rd” sound like in the English word, “card.” You simply won’t see those letters together in Yolŋu words. So using [rd] to indicate the retroflex does not create any confusion – again, IF readers know the code.

I don’t use “yirdaki” for one simple reason. The vast majority of readers do not know the code, and the result is often a much worse mispronunciation than if it had been written as “yidaki.” I’ve often heard something like:

Although some people have learned that Yolŋu emphasize the first syllable of words and say:

These have way too much [r] sound in them. We’ll hear some Yolŋu for comparison at the end. They will sound ALMOST like they’re saying an [r], but it’s much less pronounced and much quicker.

Yiragi, Yiraki, etc.

If you read old books by early missionaries and anthropologists, you’ve probably seen variations like these. I’ve seen them on lists of indigenous names of the didgeridoo. They’re not different names – just early attempts by outsiders to write “yiḏaki” before much study had been done on the language. So, to be brief, don’t use them and don’t worry about them!

Recommendation

I choose to use “yidaki” whenever possible and “yidaki” when typing on a device that makes underlining difficult or impossible. While “yirdaki” works for people who know the code, that is a tiny portion of the world’s population, so I don’t think it’s a good choice for use on the internet. People don’t know the code behind “yidaki” either, but at least it doesn’t make them say “yerdockey.” Hopefully it makes them pause and be curious, or better yet to go research it. By using only known “English” letters, “yirdaki,” on the other hand, can give the false impression that it communicates a full and proper pronunciation of the word.

Whatever you choose, at least now you understand why the confusion of a choice exists.

One More thing – CAPITALIZATION

Many people like to capitalize “Yidaki.” They consider it a special name for a special object and feel that this shows it more respect. This is not technically correct. “Yiḏaki” is not a proper noun. It is the general word for the musical instrument, just like “guitar” or “violin.” If we capitalize “yiḏaki, ” we should also capitalize other Yolŋu nouns like their words for “spear,” or “food.” It would get ridiculous. When it comes to more specific types of yiḏaki, like Dhaḏalal and Djuŋgirriny‘, then yes, those are proper nouns and are capitalized. They are to yidaki what Stratocasters and Les Pauls are to guitars. Make sense?

OK.

I hope this clears up any confusion and can serve as a reference for the future. Let’s wrap up by listening to a bunch of Yolŋu People from nine different clans say “yiḏaki,” shall we? Note that like any people of any culture anywhere, all Yolŋu don’t pronounce words the same as all other Yolŋu and individuals don’t always pronounce any given word exactly the same every time. I find the variation in the hardness and relative [r]-ness of the [ḏ] in these clips interesting.

YOLŊU PEOPLE ARE WARNED: This video contains several deceased people from the Djapu, Wangurri, Dhaḻwaŋu and Gumatj clans.