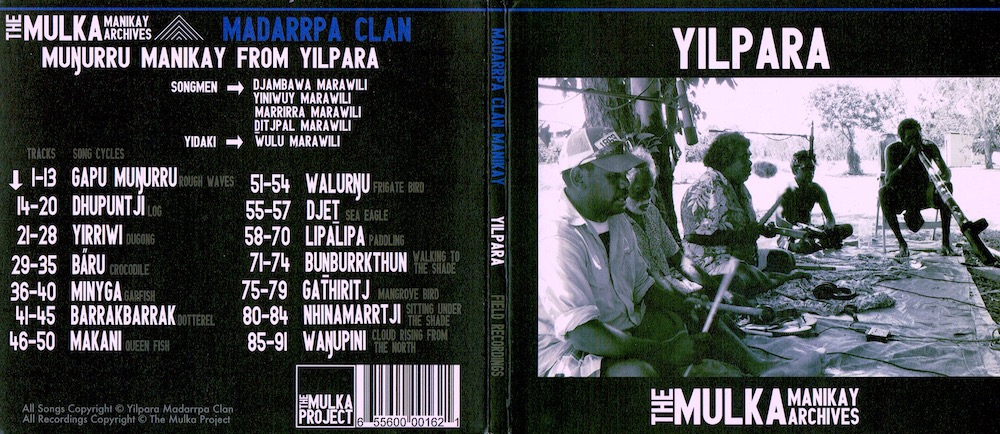

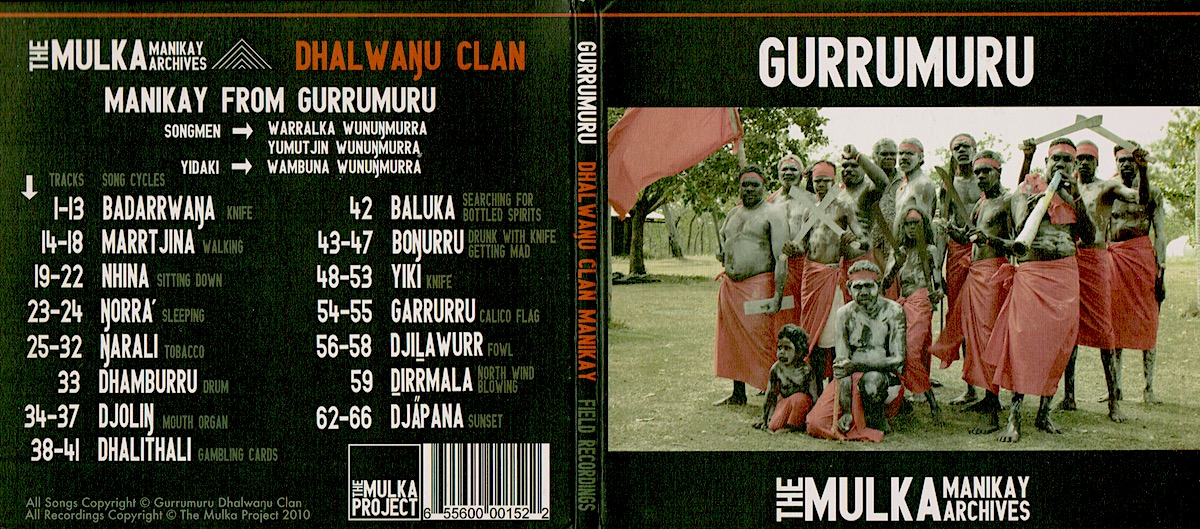

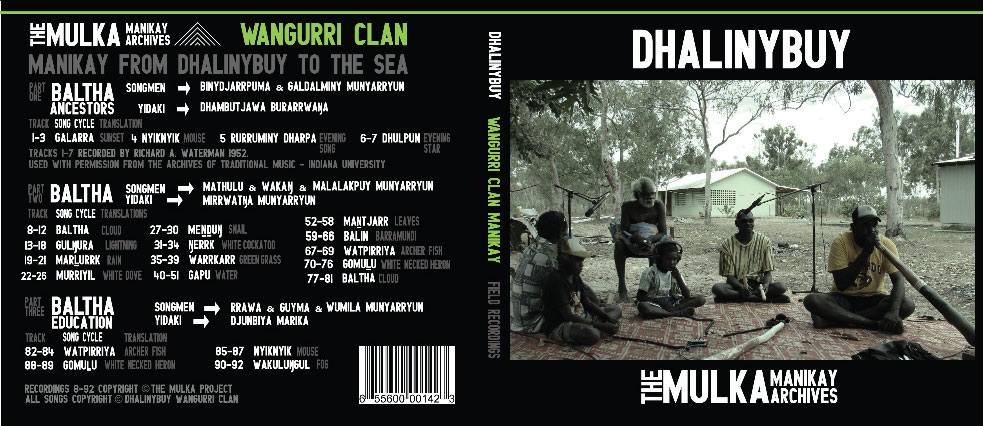

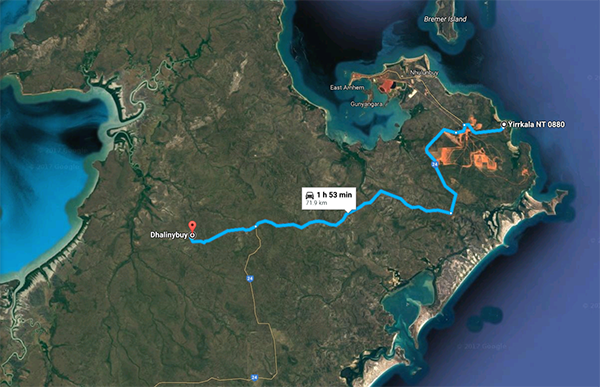

In January and February, I wrote about the first two albums I recorded for what became the Mulka Manikay Archives CD series; Dhalinybuy and Gurrumuru. In both posts, I provided some of the documentation that my Yolŋu colleagues and I created, including statements from the senior singers involved. Very little of that work was done for the last recording, Yilpara, before I suddenly had to leave Yirrkala. To complete this series on the three Mulka Manikay CD’s I recorded, let’s get some insight from relevant art documented in the book Saltwater: Yirrkala Bark Paintings of Sea Country.

In the late 1990’s, 47 Yolŋu artists created a suite of 80 bark paintings reflecting their knowledge of and connection to the sea. The people of northeast Arnhem Land started the first Australian land rights case in the early 1970’s. It was time for sea rights. Long story short, this lead to a 2008 High Court ruling which handed ownership of the intertidal zone to Aboriginal People on a large portion of the Northern Territory coast.

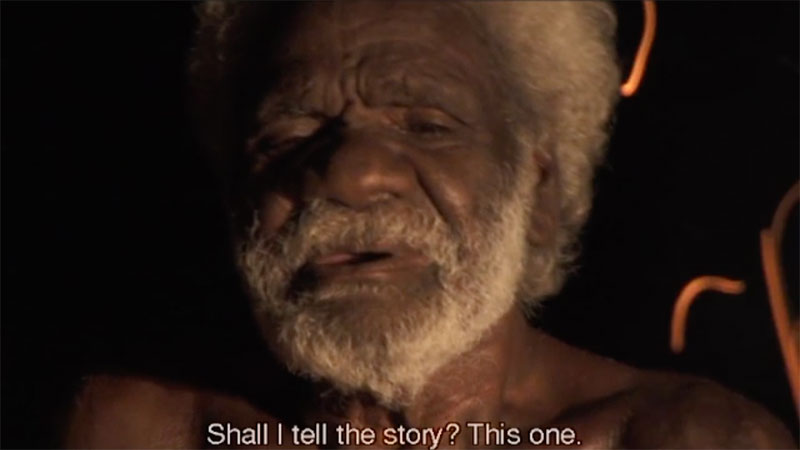

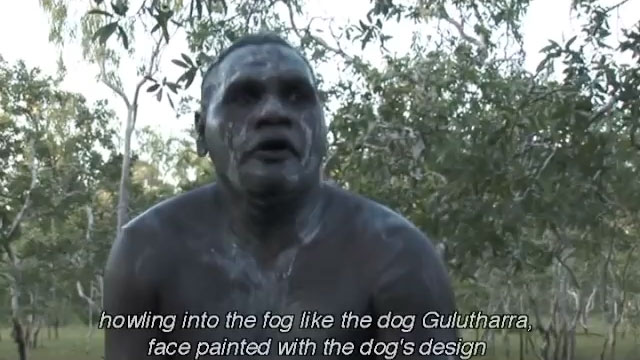

The Australian National Maritime Museum in Sydney acquired the entire collection back in 2000, and is displaying half of it now until February 2019. If you happen to be in the area, CHECK IT OUT. The ANMM’s webpage about the exhibition features this video of Djambawa Marawili, accompanied by an excerpt from his singing on the Yilpara CD. If you’ve been through the Yidakiwuy Dhäwu, you’ve heard him say similar things already.

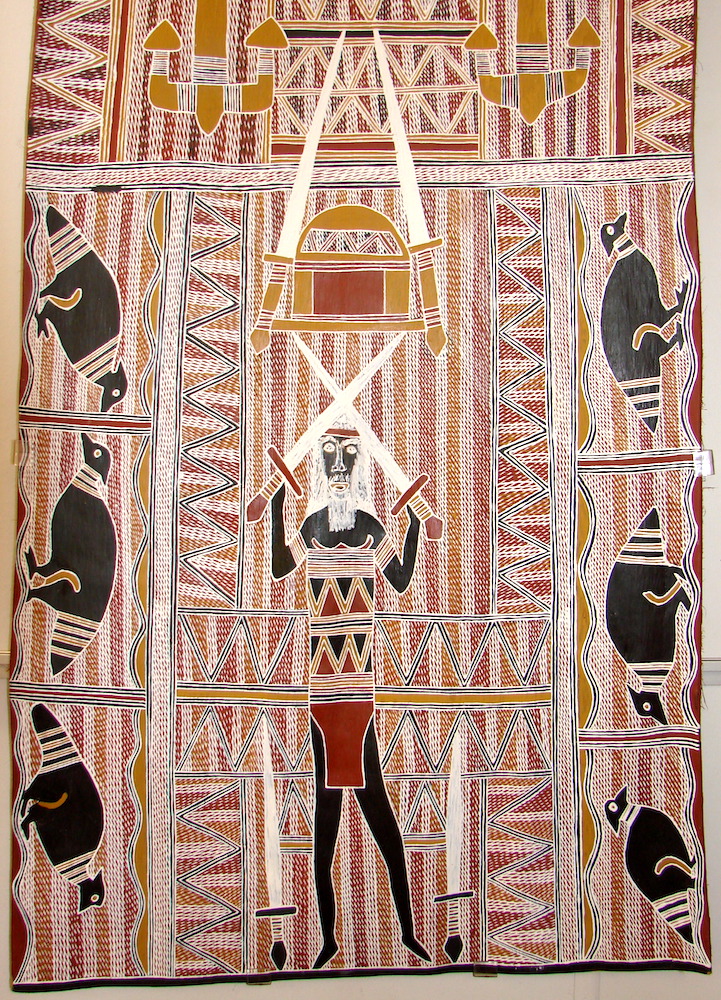

If you’ve studied this website, you may also remember the concept of the five dimensions of Rom. Wäŋa (Land), Gurruṯu (Kinship), Dhäwu (Stories), Miny’tji (Art) and Manikay (Songs). Yolŋu understand and express life through all these dimensions. Therefore, we can get insight into the songs on the Yilpara CD from stories told in paintings.

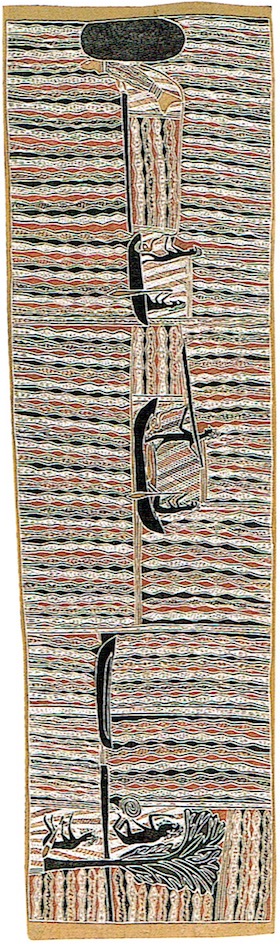

We’ll stick with Djambawa at first. His painting Gurtha at Dhakalmayi is described in Saltwater like this:

Yathikpa is an important site for the Maḏarrpa as it was here that first came to the shores of north-east Arnhem Land for the first time. Bäru, the Ancestral Crocodile power tote for the Maḏarrpa clan is strongly associated with the first fire.

Yathikpa is an important site for the Maḏarrpa as it was here that first came to the shores of north-east Arnhem Land for the first time. Bäru, the Ancestral Crocodile power tote for the Maḏarrpa clan is strongly associated with the first fire.

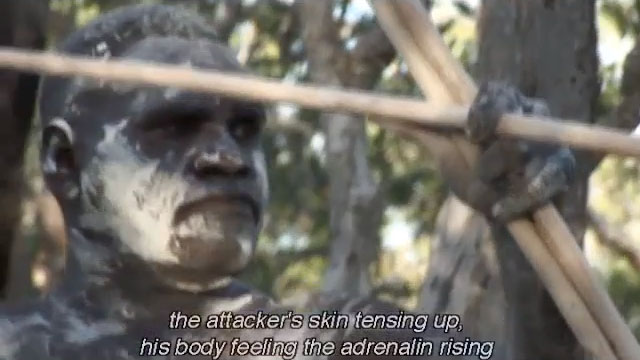

Two Ancestral beings, Burrak and Munumiŋa, took to the sea in their dugout canoe from this Blue Mud Bay coastline of Yathikpa to hunt. Djambawa has depicted them under shelter preparing to go to sea.

Once offshore and upon seeing a dugong, they pursued it. In this area of saltwater was another sacred site of fire – a submerged rock surrounded by turbulent and dangerous water. It was here at Dhakalmayi that the dugong took shelter to escape the hunters. When the hunters flung their harpoon towards the dugong, hence the rock, they enraged the powers that be, causing these dangerous waters to boil with the sacred fires underneath. The canoe capsized, drowning and burning the Ancestral Hunters with their canoe and hunting paraphernalia. The harpoon, rope, paddles and canoe are sung at ceremony and manifestations of these objects are used as restricted secret sacred objects in ceremony today.

Djunuŋgayaŋu, dugongs, are associated with this site, attracted by sandy sea beds that grow the sea grass called Gamaṯa on which they graze. In this painting Djunuŋgayaŋu is at this site around Dhakalmayi. The cross-hatched design is the sacred clan design for the Maḏarrpa representing saltwater and fire here and is a manifestation of the sacred waters and Gamaṯa waving like flames below its surface.

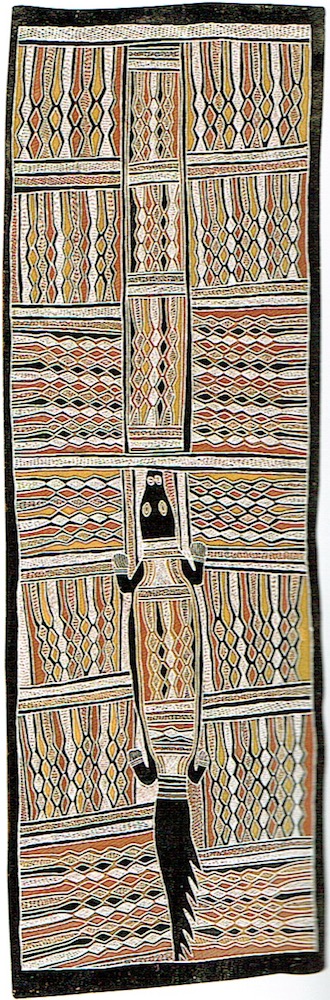

Here’s Yathikpa by Marrirra Marawili, the senior man on the Yilpara CD, which provides more clues to the inclusion of the Bäru (Crocodile) and Dhupuntji (Log) tracks.

The open-ended strings of diamonds mark the classic miny’tji of the saltwater estate of Yathikpa. Here Bäru the ancestral crocodile, carrying and being burnt by the Ancestral fire, crossed the beach from Garraŋali and entered the saltwater. After his burns were soothed, Bäru decided that he would stay in these waters. His sacred powers and those of fire imbue the water there today.

The open-ended strings of diamonds mark the classic miny’tji of the saltwater estate of Yathikpa. Here Bäru the ancestral crocodile, carrying and being burnt by the Ancestral fire, crossed the beach from Garraŋali and entered the saltwater. After his burns were soothed, Bäru decided that he would stay in these waters. His sacred powers and those of fire imbue the water there today.

Later from the same beach the Ancestral Hunters took their hunting harpoon and canoe out to the sea of Yathikpa in pursuit of the dugong. The hunters were lured too close to a dangerous rock by the dugong seeking shelter. At this sacred site fire spouted and boiled the water, capsizing the canoe. The sacred harpoon changed into Dhakandjali (YS: or Dhupundji) the hollow log coffin that floats on the seas of Yathikpa and further afield within Blue Mud Bay. It travels along the coast connecting other clans (Maŋgalili, Dhaḻwaŋu and Munyuku).

Neither of these provide you a strict narrative lining up perfectly with the track listing on the CD, but you can see the connections and understand a little of the context. To be too brief, you can look at the tracks about various fish and birds and the animals both seen by the Yolŋu, and who themselves witnessed the events of the story.

The album ends with Waŋupini, thunderclouds rising over the sea. I wish I had all the photos I took the day of the recording, but they’re all on a drive somewhere in Yirrkala. As the songs were sung, the clouds gathered on the horizon over Blue Mud Bay. I took photos on the spot that Djambawa indicated would be the album cover (reminiscent of the original Dhalinybuy cover idea). Instead, I’ll close out this post with a detail of another of his Saltwater paintings, one supervised by his late father Wakuthi. The anvil shape at center is how the Maḏarrpa clan paint their characteristic thundercloud.

This has been a very simple look at some of the Maḏarrpa clan art and story which is expressed much more deeply on the Yilpara CD. If you can find a copy of Saltwater: Yirrkala Bark Paintings of Sea Country for yourself, you will be blown away by the depth of Yolŋu knowledge of and connection to the land, and the beauty of their visual expression of said knowledge and connection. Grab a copy of that book and the CD as part of your journey of understanding the culture that brought us the yiḏaki.

All images & borrowed text above are copyright by Buku-Ḻarrŋgay Mulka Inc. and the artists. All paintings are in the collection of the Australian National Maritime Museum.

Psst. You can also listen to Yilpara here: