This post, part 2 and the forthcoming followup are based on a paper presented on April 8 at the 2017 Society for Ethnomusicology Southwest Chapter Conference. Part 1 discusses how one American ethnomusicologist’s work inspired indigenous Australians to create a new work of art including four generations of their clan.

Dr. Richard A. Waterman of Northwestern University lived with Yolŋu Aboriginal People on the remote mission of Yirrkala on the north coast of Australia while on a Fulbright Fellowship and grant from the American Philosophical Society. I can’t tell you why. Most of his published work stems from his interest in the African diaspora, including jazz, although he later co-edited a volume of papers from a symposium on change in Aboriginal Australia. Not many anthropologists visited Yirrkala before him since its founding in 1935, but many came after. Some became inextricably linked to the community’s history and are regularly referred to in the literature about the region and its people. Not so for Dr. Waterman. He never returned, was forgotten by the Yolŋu and is not often referred to by academics studying the area. However, as the first ethnomusicologist to show up in Yirrkala with a recorder and lots of tape, he left behind an unparalleled treasure trove of audio that upon rediscovery became much beloved by the Yirrkala community of today.

I did not study ethnomusicology or anthropology. My interest in Aboriginal Australia began when I started playing the didjeridu while a music composition student at the University of California at San Diego in 1993. In these heady early days of the internet, email listservs were the hot form of social media. On one of them, didjeridu players around the world emailed each other about the instrument. In 1999, only a few of us on that list in the United States were passionately interested in the origins of the instrument as opposed to its contemporary uses. One learned of the existence of Waterman’s recordings in the Indiana University Archives of Traditional Music, obtained copies of most of them through his work, and shared those with me before my first visit to Arnhem Land. On that trip in 1999, I got to know the family of renowned yiḏaki, or didjeridu, expert Djalu’ Gurruwiwi. Djalu’ loved hearing his father Monyu on Waterman’s recordings.

I earned my own Fulbright Fellowship in 2003 to follow in Waterman’s footsteps and spend a year in Yirrkala doing a Master’s project on issues of globalization and commercialization of the didjeridu. After I spent a year as a volunteer, Buku-Ḻarrŋgay Mulka, the community art centre, hired me and sponsored my migration to Australia. I brought my copies of Waterman’s recordings as conversation-starters for my research and to share with the community.

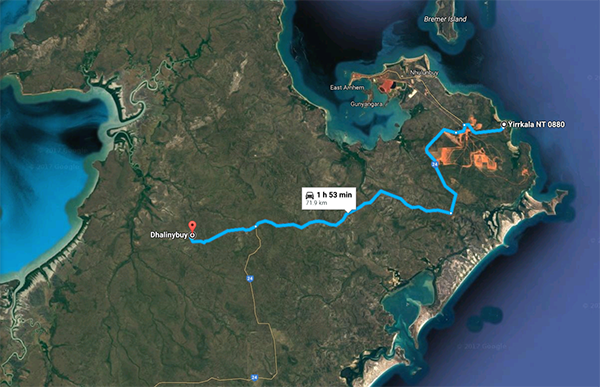

Early on, I got to know Wangurri clan families from the outstation community of Dhalinybuy (see map above). Once, in that first year there, 2004, I spotted one of the Wangurri elders, Mathuḻu, at the art centre and called him over to my desk, saying, “listen to this.” I pulled up the small collection of his clan’s songs that Waterman had recorded and played them for Mathuḻu, who calmly listened with approval and then asked for a copy.

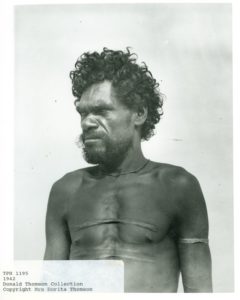

The notes on the recordings were understandably not very good by today’s standards. Waterman did not have much command of Yolŋu languages. In fact, very few outsiders did. Work to standardize the writing of the languages only began in the early 1950s. It was clear, however, that the main singer of the two men on the Wangurri tracks was “Slippery” Binydjarrpuma, a legendary warrior and sometimes renegade who was notorious right from the beginning of contact between Yolŋu and Euro-Australian people less than 30 years earlier (see works by Dr. Donald F. Thomson). Dhambudjawa, a well-known master of the day, played the yiḏaki, or didjeridu. The notes indicated that Binydjarrpuma and Dhambudjawa were joined by Galalpi.

I asked Mathuḻu about this. “It says the second singer is ‘Galalpi.’ Do you know who that is?”

He said, “yes. That should be Gaḏal’miny.”

“OK,” I replied. “Who was Gaḏal’miny?”

“He’s me.”

Mind blown. Children’s songs on the recordings included currently living people, but I did not expect to find old men still alive who sang on Waterman’s “grown up” material. Mathuḻu AKA Gaḏal’miny as a young man sang with his uncle (by our way of thinking), or second father (by Yolŋu thinking).

A few years later, I launched the Mulka Project, a new multimedia wing of the art centre dedicated to a) repatriating all the media we could about the community that had been created by outsiders into a community-accessible archive and b) training the Yolŋu to take the reigns of modern media to tell their own stories from now on. One of my first actions was to contact the Indiana University Archives of Traditional Music about getting copies of the entire Waterman Collection. They responded with great news. They were about to begin re-digitizing their entire collection and would start with the Waterman Collection for us. The new recordings were far better quality and included a lot of spoken word and secret-sacred recordings that were not in my old copies.

Around this time, one of Mathuḻu’s sons, Malalakpuy, told me his father needed a new copy of the CD I had given him. Malalakpuy hadn’t heard it, so I played the songs as I was burning a copy. He perked up and started telling me about the songs. Three were of particular interest. They told of a journey across certain of their clan lands, and of two brothers, “playing with spears.” It later came out that in fact this was the story of Binydjarrpuma journeying to a place of ritual combat to spear his own brother.

Malalakpuy came back a few days later with his brother Baṉḏamul and a proposal. They wanted to use the resources of the new Mulka Project to create a film with the two of them recreating the events described in the songs, using the old audio as soundtrack along with newly recorded song and dance reflecting the important totemic places along the journey.

This was exactly the sort of thing I wanted the Mulka project to do, and I was overjoyed that this idea had come about organically through our work. I hired two Australian film industry professionals to act as mentors for the project. Director Tom Murray spent a good deal of time in the area making his documentaries Dhäkiyarr vs. the King and In My Father’s Country. Cinematographer Bonnie Elliott participated in our first filmmaking workshop for young Yolŋu. Three of those students, Biyalŋa Biḏiŋgal, Bunbuyŋu Marika and Dhamarrarr Munuŋgurr, came along as trainee crew. We headed out for the hour and a half drive through the bush to Dhalinybuy, a remote community of less than 100 people of the Wangurri and related clans – our cast and the rest of our crew. Malalakpuy would co-star with Baṉḏamul while another brother, Banul would co-direct with him. Gurumin Marika, a senior djuŋgaya, or cultural custodian, of the Wangurri clan, would act as consultant and guide.

This concludes part 1. Part 2 discusses the film itself and the music in it. Finally, the forthcoming part 3 will discuss what went right and wrong, suggesting issues with ethnomusicology and documentation of culture. Next time, off to Dhalinybuy!

Thank you so much. I have seen some mulka project videos and have a manikay cd but i’didn t knew the story behind project.

Thank you! I’ll talk about the manikay CD series in a later article as well, especially the first one from Dhalinybuy that featured many of the same people in this article. That family were the first ones to really see how the Mulka Project could be useful.

What a great story … can’t wait for part 2!