This post, part 1 and the forthcoming conclusion are based on a paper presented on April 8, 2017 at the 2017 Society for Ethnomusicology Southwest Chapter Conference.

The Music & Logic of the Film

In Part 1, we saw how the film Two Brothers at Galarra came to be. Now let’s break down the scenes and their music to see how Richard Waterman’s recordings were used and what they inspired.

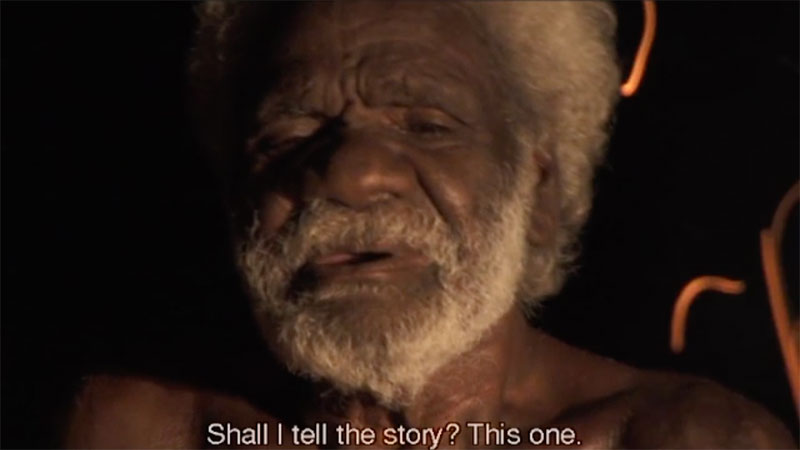

The film opens with Mathuḻu sitting by a fire, introducing the story with spoken word. As we will see later, this was in fact the last scene shot for the film. His narration also concludes the film over instrumental music carrying on from the final song. Mathuḻu’s appearance and guidance provides continuity with the 1952 recordings.

The rest of the film has nearly wall-to-wall music of three types.

1 – Dr. Waterman’s Recordings from 1952

These are of course the film’s inspiration and key soundtrack. As the film transitions from Mathuḻu’s spoken introduction to the reenactment, Binydjarrpuma and Mathuḻu sing of paperbark trees and the winds that hit them at certain places on Wangurri clan land. We see the brothers beginning their journey in country as described. The other two songs from the original recordings are far more intense. The first sets the scene for the fight to come with a long build of tension as the brothers walk through grasslands close to the ritual fighting ground of their destination. The second powerfully accompanies the film’s climactic fight.

2 – Newly Recorded Song & Dance

The second category of music in the film was performed live with the dance scenes. Supervised by Mathuḻu, Malalakpuy lead the singing with Bibibak Munuŋgurr on didjeridu. Yolŋu land is alive with ancestral stories and powers. Cycles of song & dance tell and reenact these stories. On one evening of our shoot, twenty men and boys of Dhalinybuy sang and danced the journey depicted in the film to provide this context and, in the Yolŋu way of thinking, to tell the real story. Underlying powers and spirits in the land are the unchanging reality of the Yolŋu universe despite changing appearances or modern developments. They inform and influence the actions of humans. As the two brothers in the film journey across these ancestral lands, they come to embody the powers that lie within.

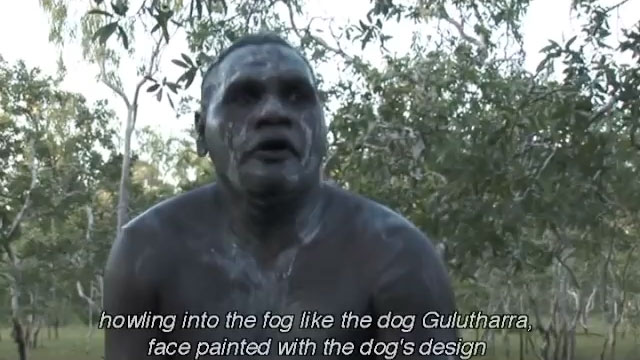

The final film doesn’t contain the whole cycle, but three key sections remain and inform a knowing audience about what’s really going on. After the first signs of tension between the two brothers, they arrive at a place of the ancestral dog Gulutharra — a role model for the Wangurri clan warrior, as we shall see in the climax and denouement of the film. Here we get a vision of the song and dance of Gulutharra. Later, the song and dance of the fighting club birku indicate that the brothers are getting psychologically ready for a battle to come. In the credits, we get the song and dance of wakuluŋgul, the dissipating fog, to show that enmity is clearing. The decision was made to let the visuals of the dances carry the full impact here, hence the lack of translation of the songs.

3 – In-Studio Sung Narration

We shot two scenes with no plan for music. Although I loved the unforgiving Yolŋu logic of the whole film thus far, we white people on set were concerned that the film would make no sense to non-Yolŋu viewers. We planned to add narration to these scenes to orient the audience. After editing the film, I brought Malalakpuy in to record the voiceover. I pressed play on the film for him to watch and started recording audio. He took me completely by surprise by beginning to sing rather than speak. Just like the 1952 and dance scene music, his song had no clear narrative, but poetry invoking Yolŋu symbols that inform what is underneath what we are seeing on the screen. This was the third type, or perhaps layer, of music in the film — in-studio sung narration. It was decided to accompany this layer of music and some of the film’s transitions with non-Yolŋu instruments to create atmosphere and further distinguish it from the other music in the film. This sung narration worked beautifully for an early establishing scene and the aftermath of the climactic spear fight.

The Finished Film

Watch the film now, whether for the first time or a more informed repeat viewing. Recognize the different types of music and how they inform what is happening, both in the surface action and the underlying psychology.

Scene Breakdown

- Opening Titles

- Mathuḻu introduces the story.

- “Binydjarrpuma” & “Nyepayŋa” walk through the paperbark forest/swamp, accompanied by a 1952 recording of Binydjarrpuma & Mathuḻu singing. The words and pictures only give the slightest hints that a conflict is coming.

- Montage of the continued journey, spearfishing, etc., accompanied by Malalakpuy’s sung narration poetically describing the scene.

- “Binydjarrpuma” & “Nyepayŋa” reach a site associated with Gulutharra, the ancestral dog which is a role model for Wangurri warriors. “Binydjarrpuma” dreams the song and dance of Gulutharra. We see the intensity and that he is disturbed about what is to come.

- The brothers proceed through grasslands close to their destination as another 1952 recording plays, the lyrics more intense and clearly indicating the conflict that is to come.

- As they near the fighting ground at Galarra, we are treated to song and dance of the fighting club Birku. This is an obvious symbol of strength and preparation for battle.

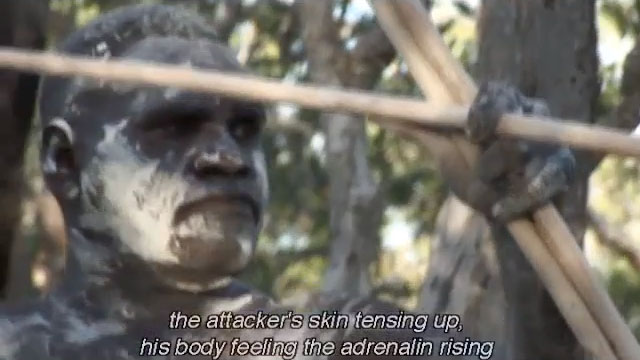

- The climactic spear fight, accompanied by the most literal of the 1952 recordings, describing the skilled warrior preparing to accept a spear.

- “Binydjarrpuma” howls and imitates Gulutharra and leaves his wounded brother behind, as described in the sung narration by Malalakpuy.

- Mathuḻu, in spoken narration, reveals that Nyepayŋa survived what was merely a ritual clearing of animosity. He needed to accept a spear and bleed, but not to die. The concluding image of the real Binydjarrpumpa and Nyepayŋa was taken by anthropologist Donald Thomson in 1942, when both men were members of the Northern Territory Special Reconnaissance Unit.

- End Titles. The men of Dhalinybuy sing and dance Wakuluŋgul, the dissipating fog, to indicate the clearing of grievances.

This concludes Part 2. In the third and final part, I will discuss what went right and what went wrong in the making of the film, and what implications it raises for the idea of ethnomusicology coming full circle.

Thanks for this video and the comments that went along with it. i did notice the shift in music during the later part of the video. I would have preferred traditional music. I found myself wanting to hear it during the dance.

The song near the end was very good. I heard the yidaki and voice together in sync. Good stuff. That singing reminded me of traditional singing I heard sometime ago among indigenous people here on Turtle Island.

I like to extend the thoughts Djambawa shared in the video here – http://yidakistory.com/dhawu/basic-information/where-does-the-didjeridu-come-from/ – to this land as well. He said Yolŋu had didjeridu and other Aboriginal People used boomerangs in the same way. Many Native Americans use drums in the same way. Not a whole band or orchestra. A droning, percussive instrument accompanying singing.

My own blood grandfathers my mother’s father’s 💚❤️