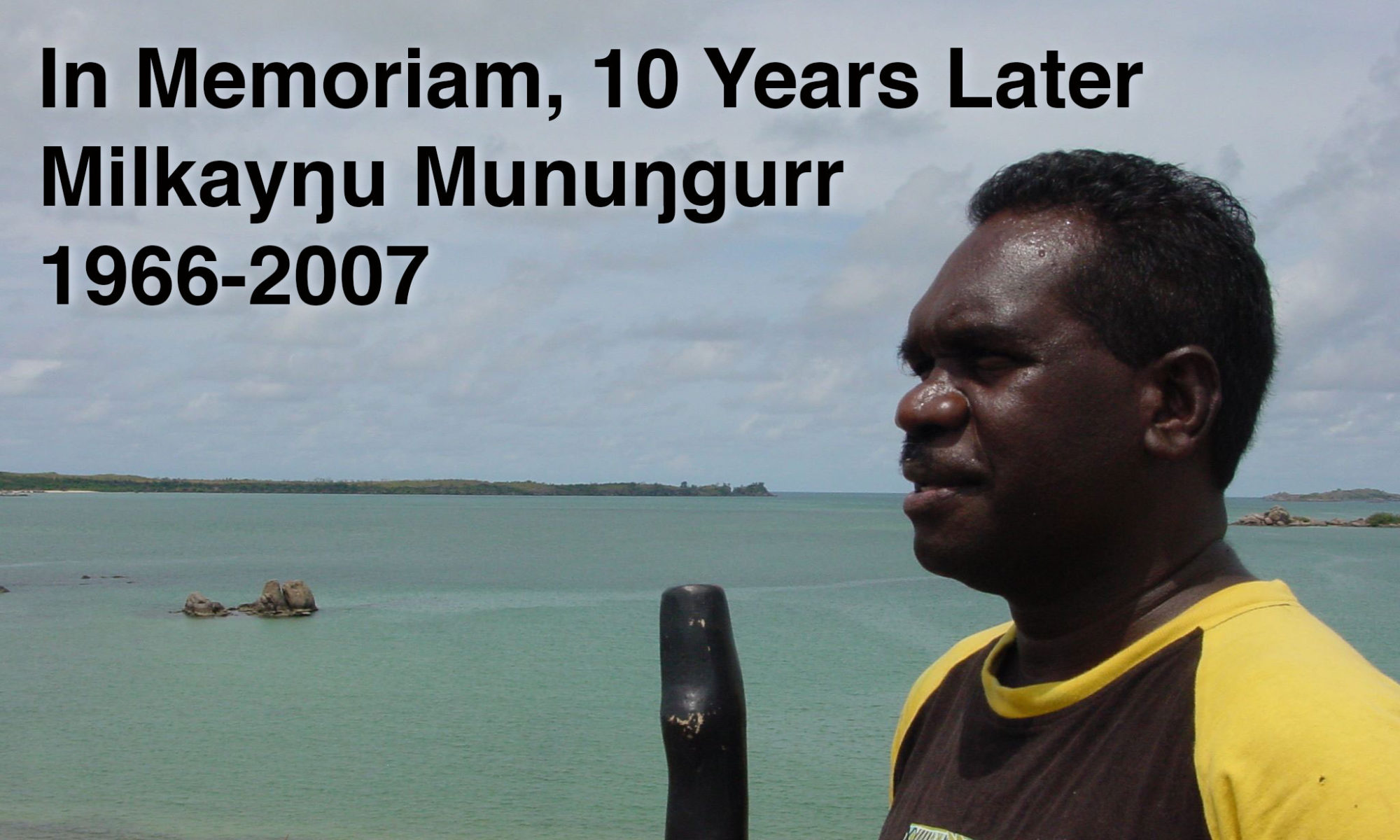

Ten years ago, we lost a legend. He may not be a household name, but few people influenced the yidaki world as much as Milkay. In the 1980s and 90s, he broke new ground in traditional yiḏaki style, inspiring young players at home and all over Arnhem Land. As one of the Yolŋu founding members of the band Yothu Yindi, a teacher, and creator of the instructional CD Hard Tongue Didgeridoo, he brought traditional yiḏaki to the outside world. Even though they might not be a big influence on younger worldwide didgeridoo players, Yothu Yindi’s popularity in the 1990s drove a lot of interest towards Yolŋu music and culture. If not for the band, yidaki may not have ever gained notice for its special place among other types of didgeridoos. Without the yidaki’s influence, we might not have the large, conical didgeridoos that are made around the world these days.

Milkayŋu Munuŋgurr was born in 1966 at the Yirrkala mission clinic, which after much renovation is now the beautiful Buku-Ḻarrŋgay Mulka art centre. His father was Mutitjpuy Munuŋgurr (1932-1993), one of the handful of Yolŋu artists who painted the historic Yirrkala Church Panels. Mutitjpuy in turn was son of the great Djapu clan warrior and patriarch Woŋgu. Milkay’s mother was Gulumbu Yunupiŋu (1943-2012), daughter of Mungurrawuy, another Church Panel painter, land rights activist and leader of the Gumatj clan. Gulumbu traveled the world as an award-wining artist, but cared deeply about maintaining knowledge at home, shown most publicly by her establishment of a Yolŋu healing centre at Guḻkuḻa.

Despite his two great visual artist parents, Milkay never took to painting. His passion lay elsewhere. “It got into me, I think. The yidaki,” he told me in 2004. “I think because it was… yidaki was my destination, eh? I was destined to play yidaki. I don’t know why.”

Milkay’s mother told him he started playing on PVC pipe when he was only 5 years old. After his dhapi, or initiation ceremony, possibly around age 8, Milkay moved to Gäṉgaṉ, his waku, or mother’s mother’s mother’s country. There, his father gifted him his first proper wooden yidaki, named Guḏurrku after the brolga, an important totem for Dhuwa people and yiḏaki players in particular.

At Gäṉgaṉ, Milkay played yiḏaki all the time, as he says in this clip from http://yidakistory.com/dhawu/yolngu-rom/when-where-and-by-who/

He returned to Yirrkala and his passion for yiḏaki grew with some new influences. He learned a lot from his Gumatj clan uncles, but his ear really perked up when he heard tapes of Dhaḻwaŋu clan ceremony at Gurrumuru – once again, his wakupulu, or mother’s mother’s mother. Dhaḻwaŋu clan players Djalawu and Burrŋupurrŋu Wunuŋmurra (read this post, too!) lead the path to a newer, more aggressive style known as yiḏaki ŋäṉarr-ḏäl, or “hard tongue didgeridoo.” Milkay studied their playing on tape, then went to live with Djalawu at Gurrumuru.

Milkay started playing yiḏaki for ceremony in his teens and quickly became a favored player for his mother’s Gumatj and other closely related clans. But his uncle Mandawuy wanted to take their culture to the rest of the world, too, and formed the band Yothu Yindi. Everything changed when a remix of their song Treaty hit the Aussie pop charts in 1991.

Plenty has been written about Yothu Yindi elsewhere, so I’ll just post two videos here. First – the clip for Tribal Voice, because it features footage of the band on the road. Milkay saw the world, and as you’ll see in a few quick flashes particularly starting around 3:30, he played yiḏaki all over the world.

Yothu Yindi performed traditional song alongside pop music. Here’s a video for Guḏurrku featuring Milkay with Witiyana Marika. Remember that Milkay’s first proper yiḏaki made by his father was named Guḏurrku.

After the initial boom of Yothu Yindi’s success in the early 1990’s, Milkay retired from the band to stay close to home and not live the rock star lifestyle. He became a ranger with Dhimurru Land Management, traveled a few times as a solo performer and teacher, and occasionally made instruments for sale when interest in yiḏaki boomed at the end of the 90’s and into the 00’s.

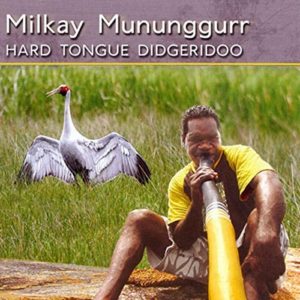

I met Milkay in 1999 but didn’t get close to him until I moved to Yirrkala in 2004. I ended up staying longer, but at the time, was on a one-year fellowship and volunteering at Buku-Ḻarrŋgay Mulka, the Yirrkala art centre. I considered creating a new volume of my instructional CD series there with a Yolŋu guest teacher, but quickly realized it would be better to make it a Yolŋu-owned product instead. I approached the coordinator of the art centre about releasing it and Milkay about creating it, and plans quickly came together.

A future blog post will talk more about the creation of Hard Tongue Didgeridoo. For now, note the cover. Milkay insisted on Guḏurrku making an appearance with him.

Also featured: images with his gäthu, or son, Buyu and crossed yiḏaki symbolizing the transfer of knowledge. With these images, Milkay acknowledged his father, his deeper totemic identity, and the passing of knowledge to future generations.

He took me under his wing a bit as we got to know each other through the CD project. We had some good times and he taught me a lot… but those might be subjects for future blog posts.

Milkay struggled with alcoholism and depression like many of the disenfranchised people of Arnhem Land. Many people knew him a lot longer than I did, but I feel like I saw him at both his best and his worst in his last few years with us. For one thing, as a Djapu clan man, he was a shark. He was born of a Gumatj woman – a crocodile. He definitely embodied these ancestral totems. These raw powers of beauty and sudden aggression. But he was also a big softie.

I’ll share one personal story I’ve only told privately to a few people. Our first trip together was in October 2004. Thanks to the Australian-American Fulbright Commission, we went to Canberra for a reception with the US ambassador, spoke at the National Museum of Australia and on ABC radio, and got to look through the NMA’s collection of yiḏaki. We stopped on the way back for a workshop in Sydney. Milkay indulged in alcohol now and then during the trip. It wasn’t a problem to that point, but he took it too far that last night, getting very drunk during the workshop. We spoke about it on the plane home the next day. I tried not to be too preachy. I told him that he was an adult and free to do what he liked, but that he should remember that he was representing his people, the yiḏaki and his entire culture at events like this. The conversation was brief and to the point. He acknowledged it but we didn’t dwell on it.

Our next trip was in June 2005, to teach yiḏaki workshops at the first Dreaming Festival in Woodford, Qld. It was four days, and everything went smoothly. After the last workshop finished, he started drinking, celebrating big time. It took a herculean effort to get him on the plane the next morning, but we made it. Then he totally shocked me on that flight by bringing up the conversation we had on the plane home from our previous trip eight months earlier. He told me he remembered everything I said and didn’t want to let me or his people down this time, so stayed sober until the work was done. I almost cried. I knew this was a person with human failings but deep integrity. A person I wouldn’t give up on.

He continued as a person of extremes after that. He attempted suicide at least once then got sober for an extended period, about 7 months. It seemed a huge step. He had seen the outside word, seen different ways to live and could see a better way for his people. But the situation in Arnhem Land was too much for him. He got caught back up in the self-medication that is so common among his people as they try to survive their existence, stuck between two worlds, not knowing what the way forward could be.

Two years later, in June 2007, we returned to The Dreaming with a group of about a dozen Yolŋu to perform and present various workshops. The Yolŋu music world took a big hit while we were there. Gumatj clan singer George Rrurrambu of Warumpi Band fame passed away from lung cancer at Galiwin’ku. When word came through to the festival and our group, Milkay took on a new leadership role. As senior djuŋgaya/child of the Gumatj clan present, it fell to him to make sure protocols upon the death of this Yolŋu man were followed by our group, and by extension by everyone at this Aboriginal-themed festival. He liaised with festival organizers to put out the word that we wouldn’t be saying his name, playing his music, etc., and led a public memorial ceremony. He had spoken to me earlier about wanting to move away from playing yiḏaki and start to sing as a leader. He did that at the Dreaming in performance and in this brief ceremony. I was proud of him.

Meanwhile, funeral ceremony was ongoing back home for his own sister who had passed away from cancer. As the festival closed and it was time to head back home, Milkay didn’t want to go. He didn’t want to get dragged back into the old cycles of depression and drinking back home. He wanted to stay with his cousin who lived nearby in Brisbane, attending boarding school. He of course had been drinking at this time, so it was hard to say if he was in any state of mind to make such decisions. I did my job and rallied the group to get him on the plane, reminding him that he needed to get home for the close of his sister’s funeral.

A few weeks later, on a peaceful Sunday morning in July 2007, Milkay went fishing. Everyone said he seemed peaceful and happy. He returned home and took his own life. I got a call hinting at what happened and saying I should hurry from Yirrkala to Gunyaŋara’ to see him. The car horn started blaring around Yirrkala announcing a death. I couldn’t get myself to rush so just made it in time to be part of the procession to the hospital. I can’t say exactly what I felt, but I didn’t feel the need to see his lifeless body. I wasn’t particularly upset or sad in that moment. I remember mostly thinking that at least he could finally rest now, and being glad that I got to be part of his last few years here.

A few weeks later, on a peaceful Sunday morning in July 2007, Milkay went fishing. Everyone said he seemed peaceful and happy. He returned home and took his own life. I got a call hinting at what happened and saying I should hurry from Yirrkala to Gunyaŋara’ to see him. The car horn started blaring around Yirrkala announcing a death. I couldn’t get myself to rush so just made it in time to be part of the procession to the hospital. I can’t say exactly what I felt, but I didn’t feel the need to see his lifeless body. I wasn’t particularly upset or sad in that moment. I remember mostly thinking that at least he could finally rest now, and being glad that I got to be part of his last few years here.

It has now been ten years since Milkay passed away. Part of me wonders what he would be doing now if he were still with us. Part of me is satisfied he completed his journey and is at peace. Both parts miss him. Both parts are grateful for what he accomplished and shared both with the world and with me, personally.

I’ll leave you with a world premiere. In 2006 as we were shooting video for Yiḏakiwuy Dhäwu Miwatjŋurunydja, he mentioned his aspiration to graduate from yiḏaki player to a singer, leading ceremony rather than accompanying it. We did a hasty recording of him playing and singing – what else – Guḏurrku, the brolga.

Continue to rest in peace, my friend and teacher.