With the news of another death in the yiḏaki world, perhaps it is time to talk about death in Yolŋu culture. This post scratches the surface of this huge topic and introduces you to some basic concepts and protocol.

First, the News

A great Yolŋu yiḏaki player and maker passed away last week. As I’ll discuss below, Yolŋu custom forbids speaking the name of the deceased for a period of mourning. I believe it is a bit extreme to apply this to typing on the internet, but for those who are sensitive about it and in case any Yolŋu family read this, I’ll just type the first name here once in white text. Datjirri #1 Wunuŋmurra. Double-click or hold your finger on that white space to select the text and see the name.

Find more information about Mr. Wunuŋmurra on the old Yirrkala Yiḏaki website, thanks to the internet archive. He was talented, knowledgable, charismatic, funny and lots of trouble, and I will miss his presence when I’m in Arnhem Land. I will never forget the sparkle in his eye as he said, “let’s go shopping,” whenever we went out to cut yiḏaki.

Bäpurru

When a death occurs in northeast Arnhem Land, word goes out about a bäpurru, in this case meaning “a death.” Bäpurru is also the main word for “clan” in Yolŋu languages. Individuals identify the bäpurru to which they belong, such as Djapu, Gumatj, Gälpu, or in Mr. Wunuŋmurra’s case, Dhaḻwaŋu. I can’t explain to you why Yolŋu use the same word for “clan” and “a death.” I made a quick scan of my library and didn’t find any clear explanation from academics. The best guess is that it stresses the kinship connections between everyone and suggests “a death in the family.”

In short, if a Yolŋu person tells you, “_______ is my bäpurru,” they’re telling you their clan affiliation and therefore, in many respects, their very identity. If someone says something like, “did you hear about the bäpurru?” they’re alluding to news of a recent death.

Use of Name & Images

Yolŋu do not go around telling everyone, “hey, John just died.” No one utters the name and no one is told in such a matter-of-fact manner. Families gather and are sung the news. Leaders bang the biḻma, or clapsticks, with particular patterns and sing songs that indicate the person’s lineage (including their own bäpurru). On at least one occasion I witnessed, this song was followed with a few words to clarify a potential ambiguity, such as which of two brothers died. Upon hearing the news, women begin to wail and sing milkarri – crying songs. They improvise words to clan melodies to mourn and celebrate their connection to the deceased. Find a little more info and a video clip from the film Bulunu Milkarri HERE.

Why do they not say the name? On a simple level, to avoid upsetting surviving relatives. On deeper levels, there are two main reasons corresponding to two different Yolŋu concepts of the soul.

Birrimbirr refers to a good spirit that leaves the body of the deceased to journey back to its home. For some clans, this is a water hole on sacred land. For others it is said to be an island of spirits to the northeast. Others speak of the stars in the Milky Way as the souls of departed clansmen. From this reservoir of souls, this birrimbirr may leap into the body of a pregnant woman later on. Calling out the deceased person’s name may distract the birrimbirr from its journey and break the cycle of spirits coming into humans to keep the clan alive.

A darker, perhaps trickster part of the soul is referred to by the general word for spirits, mokuy. This spirit lingers after death. It haunts the deceased’s home, workplace and possessions. Calling out the name of the deceased might get the attention of this mokuy and bring “spiritual pollution” to close relatives, causing injury, illness or even another death. Shortly after the death and the ensuing funeral ceremony, Yolŋu perform cleansing ceremonies with water or smoke to wash away this spiritual pollution. If you visit a Yolŋu community, you may see houses or vehicles with traces of red bands painted around them. This indicates that they were cleansed following ceremonial business.

Yolŋu integrate introduced technology such as photographs and audio recordings into these customs. These new media remind families of the deceased and may invoke the spirit. However, not all Yolŋu feel the same way about this. Many privately collect, view and share photos of recently deceased kin. On at least one occasion, family chose to display a portrait of the deceased at a memorial service, to mixed response from Yolŋu in attendance. Rules are often bent for Yolŋu who rose to prominence outside of Arnhem Land. Family of the late lead singer of Yothu Yindi allowed his image to be displayed much sooner than normal, and the late George Rurrambu of Warumpi Band insisted while dying from lung cancer that people keep playing his music and showing his image.

Yolŋu also avoid words that sound like names of the deceased. Didjeridu players may remember a few years ago when the word yiḏaki was not to be spoken because it is one letter away from the name of a deceased man. The alternate word mandapul became prominent at that time in the area around Yirrkala, but yiḏaki is clear for use again.

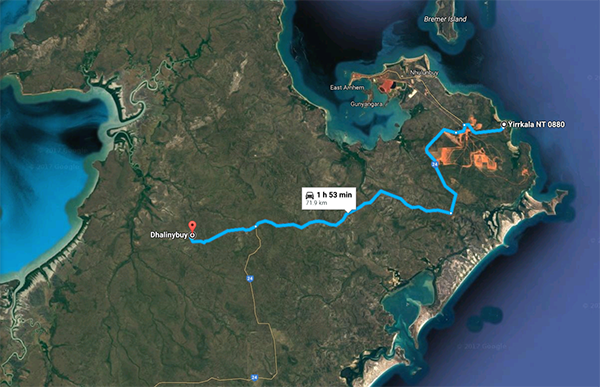

The mourning period varies widely from a few years to a decade, and may vary between different people across the region. Close family avoid a name or word for longer than other Yolŋu will. Yolŋu from the west of the region, at Milingimbi, for instance, most likely continued using the word yiḏaki as they were not close to the man with the similar name who passed away in Yirrkala, on the eastern edge of Yolŋu country.

The best advice, however, is to err on the side of caution to avoid upsetting anyone. If you are physically with Yolŋu people, speak with caution. Do not post photos or video and audio recordings of recently deceased Yolŋu people. As for typing names of the deceased on the internet, I was once told, “spirits don’t read.” I’d wager that typing a name will not distract a spirit from its journey. But sensitive family members or overprotective outsiders may happen across it.

What Happens When Someone Dies

When death is near, families gather and sing songs to prepare and soothe the dying person. Buwathay Munyarryun speaks about that here, in a video clip from http://yidakistory.com/dhawu/yidaki-issues/healing-with-the-didjeridu/.

In the old days before European influence, Yolŋu painted the deceased body with sacred designs of the person’s lineage while song and dance continued. After this first round of ceremony, bodies were left in shallow graves or tree platforms to decay. Later, family returned to collect the bones and paint them. Key parts such as thigh bones and skulls were bundled in paperbark and carried for a time, perhaps a year. Then, in a final round of ceremony, hollow log coffins known by various names such as ḻarrakitj, ḏupun or dhakandjali were painted with sacred designs of the deceased’s lineage. Yolŋu placed the bones in these coffins for final disposal and left them in the bush to decay.

With the introduction (imposition?) of quicker in-ground burial, modern Yolŋu mortuary procedures are a bit condensed. Singing begins around the body as families are notified all over the region. Usually, if the death is in or near Yirrkala, the body is ceremonially carried to a vehicle for a slow procession to the hospital in the mining town of Nhulunbuy. On arrival, song and dance escort the body from the vehicle to the morgue. Families then plan the funeral ceremony, then at the appropriate time, return to collect the body and again ceremonially escort it from the morgue to the vehicle and from the vehicle to its resting place for the ceremony. The body is ritually guided at every movement. Long distances complicate this, such as deaths in remote homelands or major cities like Darwin. Every movement from house to car to plane to car to hospital to morgue must be accompanied ritual song and dance.

Funeral ceremony lasts anywhere from a few days to a few months depending on the person’s significance and the amount of family involved in the ceremony. The deceased own clan, mother’s clan, mother’s mother’s clan and djuŋgaya (see http://yidakistory.com/dhawu/yolngu-rom/yothu-yindi/ for more info) take primary roles, but more distant relations may also be involved. Other ceremonies such as boys’ initiation often piggyback on funerals to take advantage of the large gathering.

Every funeral is different. Leaders of the concerned clans gather and decide the needed series of events. Each day brings new cycles of ritual song and dance that aim to guide the spirit to its resting place. Related clans take turns doing their part. Intensity builds until the climax of the burial. Designs once painted on hollow log coffins now adorn coffin lids and grave markers. In the days following the burial, ritual cleanses the mourners, particularly those who handled the body, of any spiritual pollution.

Cleansing ceremony after a funeral in Yirrkala, 2007.

Cleansing ceremony after a funeral in Yirrkala, 2007.

Further Reading & Viewing

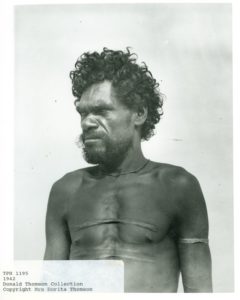

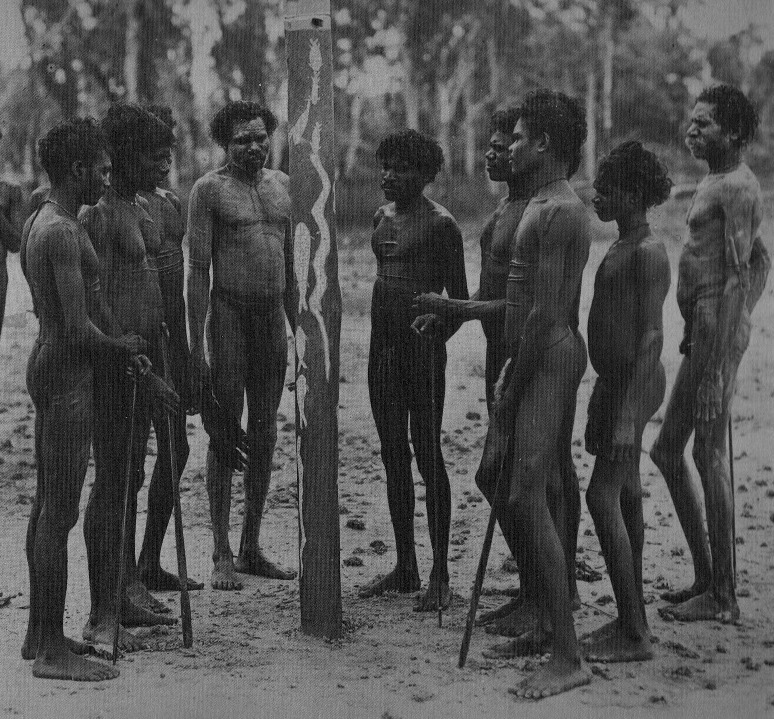

The legendary anthropologist Donald Thomson, who worked in northeast Arnhem Land in the 1930s, wrote that if he could fully understand Yolŋu funeral ritual, he would have the key to a full understanding of the whole culture. The quest for that understanding continues today.

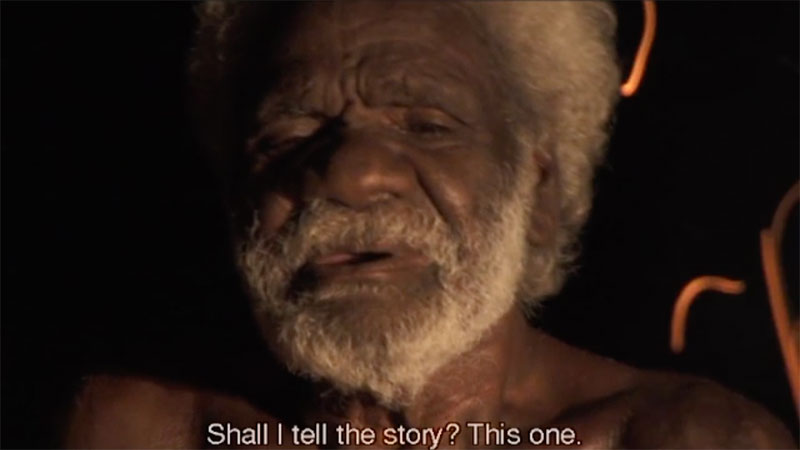

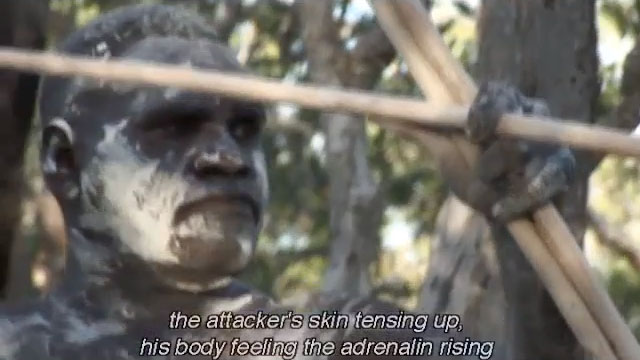

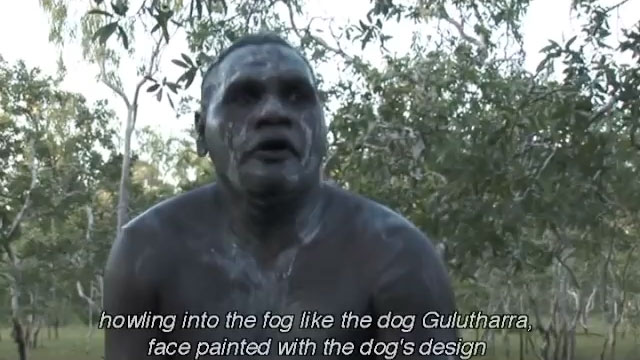

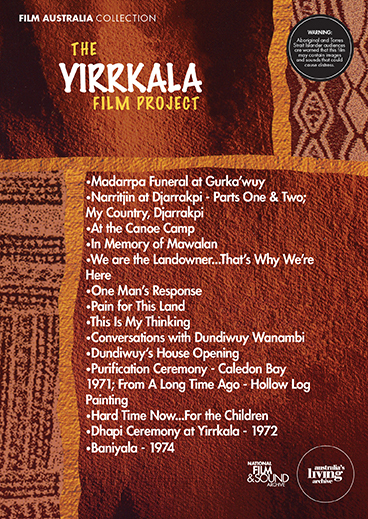

If you want to delve deeper into this, my number one recommendation comes in two parts. The film Madarrpa Funeral at Gurka’wuy by Ian Dunlop and the book Journey to the Crocodile’s Nest by Howard Morphy both document one Yolŋu funeral from 1976. The film allows you to see and “experience” some of the action for yourself while the book has more time to fill you in on the background. Morphy discusses in detail who participated and why, and what micro-ceremonies added up to create the whole funeral. Combining the strengths of written word and visual media to cover one ceremony conveys more understanding than any one film or book can alone.

That said, neither are easy to come by, even in Australia. Search for the book at libraries, particularly university libraries, and online used book websites. The film is part of the Yirrkala Film Project, a series of 22 films shot throughout the 1970s. Again, look at libraries near you, but don’t expect much outside of Australia. If you are seriously interested in Yolŋu culture, I highly recommend that you purchase the entire series HERE. You will learn so much. I got my hands on most of the series between my first and second visits to Arnhem Land in 1999 and 2001. Viewing the films greatly improved my knowledge and ability to communicate with Yolŋu.

Two of the photographs above by Donald Thomson are available in the beautiful book Thomson Time: Arnhem Land in the 1930s – A Photographic Essay. You should buy it.

Two of the photographs above by Donald Thomson are available in the beautiful book Thomson Time: Arnhem Land in the 1930s – A Photographic Essay. You should buy it.