This post takes us out of yiḏaki country and therefore outside the main goals of this website, but I can’t help it. I admit I haven’t researched this thoroughly and don’t know if this has already been debated in academic circles, but the idea keeps showing up in my social media feeds, so I’ll provide my thoughts here.

It has long been accepted that the word didgeridoo or didjeridu is onomatopoeic – a term coined by Europeans to describe the sound the instrument makes. Back in 2002, articles started going around about a theory from Flinders University PhD student Dymphna Lonergan that the word didgeridoo could have its origins in the Gaelic language. The words dudaire (piper) and dubh (black) can be combined into something resembling the modern didgeridoo.

On one hand, I like it. It’s a fun idea. But here’s the thing. I don’t buy it. At all. Here’s why.

First: Coincidences Happen

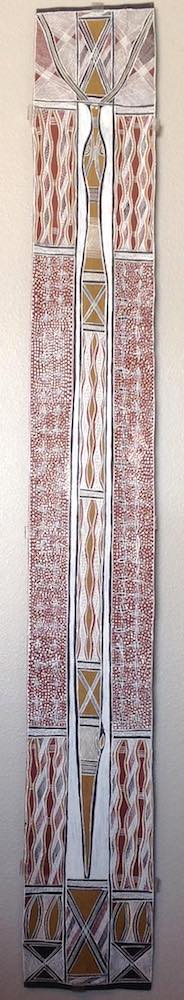

To briefly ground ourselves in this blog’s home country of northeast Arnhem Land, here’s one of the few bark paintings I bought for myself while I was a coordinator of the Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Art Centre in Yirrkala. It’s by Baluka Maymuru, whom you can hear singing with yiḏaki on the Mulka Project CD Yiŋapuŋapu. The Maṉgalili clan sing, dance and paint the river Milŋiyawuy, which is paralleled in the night sky by the stars of what we call in English the Milky Way Galaxy. I find the similarity of the terms Milŋiyawuy and Milky Way quite striking, but I have no doubt it’s coincidence. Yolŋu would say the term Milŋiyawuy was given by ancestral beings at the time of creation. The name Milky Way, though obviously an English translation, has its origins in Greek myth. I don’t see any way that these terms could have influenced each other.

Second: Historical Context

The researcher stated that in an experiment, “asking subjects to make the sound of the instrument yielded words full of vowels starting with the letter “b” or “m”. No subjects made the sound didgeridoo.”

Now there’s a little detail that I trust is obvious to anyone reading this blog that was not taken into account by the researcher. If you ask average people around southern Australia or anywhere in the world to think of the sound of the didgeridoo, they’re going to think of the crisp drones or “womble” rhythms of mainstream contemporary didge playing.

Nope. It doesn’t sound like “didgeridoo.”

But if we’re talking about the origin of the word didgeridoo, we’ve got to go back to the first European settlers having their first contact with the instrument. Traditional didge snobs reading this blog know what that means.

Here’s Dr. Alice Moyle’s map of the traditional origins of the didgeridoo, based on her field work in the Top End in 1962-3. It’s widely accepted as fact that the didgeridoo’s use was limited to roughly this area at the time of European contact. Dr. Moyle identified two main styles of playing in that region, the western A-type and the eastern B-type. Basically, A is non-Yolŋu playing that many didge fans around the world know as mago style, and B is Yolŋu yiḏaki style.

European settlement of the Top End came overland from Alice Springs to the south and via the sea mostly to the central part of the Northern Territory. There we find the failed early attempts at settlement near what, in an eventual success, became the city of Darwin. This is all firmly in the territory of Dr. Moyle’s A-type didgeridoo style. This is the first didgeridoo playing that was regularly heard by Europeans.

What does that sound like? Here’s the late great David Blanasi playing in 1962.

And here he is singing the rhythm.

Unlike the subjects interviewed by the Flinders University researcher, anyone familiar with this style of didgeridoo playing would indeed start an imitation of the sound with a ‘d’ instead of a ‘b’ or ‘m’ and would most likely in fact start with the syllable ‘didj’.

Third: Historical Record

The Gaelic origin of didgeridoo theory is just that – a theory, based only on a coincidence. There is no historical record I am aware of to support it. On the other hand, records exist to support the onomatopoeia theory. Didgeridoo didn’t start appearing in dictionaries until 1919, but the term’s origin could be as much as 90 years older than that.

Collet Barker was an English military officer and ‘explorer’ of Australia. He developed better relationships with Aboriginal People he encountered than most Europeans did at the time, including during his brief tenure as commandant of the short-lived Fort Wellington on the Coburg Peninsula, the top center of the Northern Territory’s Top End. Firmly in Moyle A-type didgeridoo country. He wrote, circa 1829:

Mago had brought a kind of musical instrument, a large hollow cane about 3 feet long bent at one end. From [this] he produced two or three low & tolerably clear & loud notes, answering to the tune of didoggerry whoan, & he accompanied Alobo with this while he sang his treble. source

‘Didoggerry whoan’ is clearly similar to didgeridoo. It is specifically how an early European visitor to Australia’s Top End described the sound of the instrument. Perhaps it is the earliest extant written description of the sound. This obviously supports the standard onomatopoeic origin story for the word didgeridoo.

In Conclusion

I don’t mean to be a spoil sport and have nothing against the person who came up with the Gaelic origin theory, or anybody who finds it fun to think about. But all this context seems important and instructive, so I thought it should be stated all together at least somewhere on this crazy internet. If anyone has more information to share on the subject please do so!

Thanks for that research (again), and your two cents. I like your writing.

Thanks!

Excellent article and well supported. I am a respected follower of your research having spent my own time collecting and recording in NE Arnhem Land. Happy to see your documentation of styles and artists.

Thank you, James.

Hello Randin_ I came to the same conclusion. I am puzzled by the term itself “Mago”. As referenced in the material you have offered, it appears to be a person’s name. Do you know more about this? Trying to find out what it means (literal translation in English). Thanks.

I don’t know anything about that, I’m afraid. And it’s hard to say if the name “Mago” in the quote from Barker’s journal is more than coincidence. He was an Englishman who was there about a year, so obviously didn’t really know the local languages, and there was no standardization for writing them, anyway. And for all we know, “Mago” wasn’t even the guy’s name. I’ve come across (and been part of!) many cross-cultural misunderstandings. Someone might have said, “him called ‘mago’,” referring to the didjeridu itself, not the player.

I’m not sure how widely the word “mago” is used for didjeridu. It was largely popularized to westerners by David Blanasi, who identified as Miali. With a quick googling, I see Mayali as another word for Kunwinjku languages, which could have been used up where Barker was.

And again, I don’t know about “mago” in Kunwinjku, but I asked many Yolŋu if “yiḏaki” had another meaning, and they all insisted that it was just the name of the instrument.

Thanks for looking into this Randin. It ain’t easy.