This concludes a three-part series. Read part 1 HERE and part 2 HERE.

Ethnomusicology Coming Full Circle – Success & Pitfalls

Two Brothers at Galarra is on many levels a successful story of ethnomusicology coming full circle in a time when old documentation is being repatriated and formerly “primitive” people are telling their own stories. An American ethnomusicologist’s recordings inspired members of the Wangurri clan, living in a remote bush community, to create new art in a modern medium. Families united in common purpose. From Binydjarrpuma on tape and in an archival photo to young boys in the dance scenes, four generations of Wangurri clansmen appear in the film. They celebrated their ancestors and their culture. Indigenous people created a new document for their own future generations.

Truth

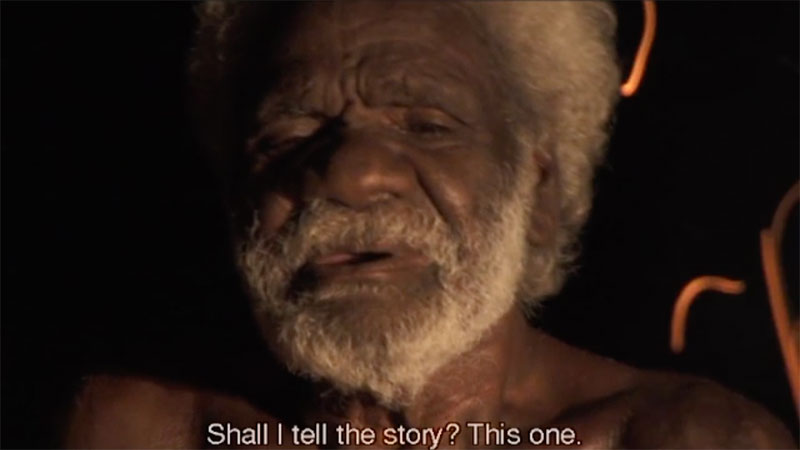

The film also reveals some of the pitfalls of documenting previously oral cultures and using these documents as sources of “truth.” We began shooting the film by setting up around a fire and asking Mathuḻu to tell the story, partly to capture his narration for the film and partly for the white crew to learn the story. With my limited grasp of his Wangurri dialect, I suspected, but wasn’t sure, that something wasn’t quite right. Gurumin and Malalakpuy confirmed this when translating the story immediately afterwards. Mathuḻu told the sequel – the next part of the story that we were not there to film. But everyone told us it was OK. We could move on. The younger men knew the story. Binydjarrpuma killed his brother Djalatharra in ritual vengeance.

On the last day, we decided to try again to film Mathuḻu telling the story to use as either a frame or narration throughout the film. This final recording of Mathuḻu revealed that his sons might have combined elements of two different incidents. They were thinking of Binydjarrpuma and Djalatharra, but Mathuḻu declared in his second session that the songs described Binydjarrpuma and Nyepayŋa, a brother from the same mother but a different father – in fact a father from a different clan, the Dhaḻwaŋu. On one level, we simply lost a visual opportunity. The Dhaḻwaŋu brother should have worn a red loincloth rather than the Wangurri green that they both wore. Worse, we got a major plot detail got wrong. Nyepayŋa was speared in a ritual clearing of animosity for a past wrong, but he was not killed. Drawing blood was good enough to erase the debt. Our film ended with him lying on the ground motionless for several minutes. Yolŋu are very sensitive about their stories and tales of trouble between ancestors. We got the story wrong and we had not in any way consulted with the Dhaḻwaŋu, including Nyepayŋa’s many living sons. As Mulka Project coordinator and the film’s editor and producer, I had a tough job of diplomacy ahead in order to save the project.

It seemed at first that Malalakpuy, Baṉḏamul and Banul did not know the whole story and got the film wrong. We acted accordingly and adjusted the best we could. I consulted with one of Nyepayŋa’s eldest surviving sons, re-edited the ending and recorded new narration with Mathuḻu to close out the film. Later, I realized that the song in the climactic spear fight says clearly that a Wangurri warrior dodges the spears while preparing to accept one. Not a Dhaḻwaŋu warrior. Perhaps the young men had the story correct, and the elderly man who sang the song 55 years earlier got it wrong. Mathuḻu has now passed away. We can’t ever know whether the story Mathuḻu told is “truth.” Yet nothing would have happened at all if the project had not happened in his last years.

The songs are poetic, telling the story symbolically rather than through a literal narrative. Yolŋu can not be certain what the exact events were. Documenting a culture doesn’t preserve the culture, either as a whole or even the whole truth of any one small event. It creates snapshots that are no substitute for living, breathing culture. We did what we could to correct our error in post production, but even this Yolŋu-made film now serves as a not 100% accurate document for future generations.

This specific case is perhaps not so significant. It is not the end of the world if this one story is not maintained 100% accurately. The issue becomes more significant as indigenous cultures try to recreate ceremony and languages from documentation created before missionaries and other outside influences changed cultural practices. I reflect on this with each new call for academics to record song or languages “before it’s too late.” What is being preserved and for whom? Perhaps it does not matter if these songs or languages are performed “correctly” in the future. Perhaps all that matters is people are alive to try and use them, and some documentation for inspiration is better than nothing. Still, the more time I spent in Arnhem Land, the more drive I felt to work against issues that disrupt culture and cause its loss or change, rather than to spend my time documenting the culture.

All that said, the people of Dhalinybuy and I will remain eternally grateful to Dr. Richard A. Waterman for his research and recordings that inspired Two Brothers at Galarra. It was clearly a valuable and moving project for the people of Dhalinybuy, with the community dance scenes as a highlight. Apart from the value of showing the poetry of Yolŋu philosophy on film, these scenes included three generations of Wangurri kin. With Waterman’s recordings of Binydjarrpuma, that’s four, with Mathuḻu as the link. This is the truly glorious moment of ethnomusicology coming back to the community. It inspired a project to pass down a story and create new art in a participatory way through several generations.