Yes, I’m going there. The issue that won’t go away. And has no answer.

Should women play didgeridoo?

Yiḏakiwuy Dhäwu Miwatjŋurunydja addresses the issue at www.yidakistory.com/dhawu/yidaki-issues/women-play-didgeridoo. In conducting interviews and writing the basic text for the Dhäwu, I aimed to represent the range of views in northeast Arnhem Land as much as possible. To summarize, key male figures in the Yolŋu yiḏaki world like Djalu’ and Burrŋupurrŋu invite non-Aboriginal women to learn to play from them. Baḏikupa and Djambawa speak of Yolŋu women playing in ceremony in older days when no men knew the songs. Wukuṉ, on the other hand, believes that women should not and are in fact incapable of playing. Three women, Banduk, Merrkiyawuy and a late sister of Djalu’, share a range of opinions but all agree that Yolŋu women will stick to their traditional women’s business. Only Banduk says strictly that outsider women should never play didjeridu, while the other two leave some room for personal choice.

On this blog, I share my own experiences and views – and in this case, those of my wife, Brandi – instead of strictly representing Yolŋu opinions. I asked Brandi if she would write a guest post, but she passed and told me to write this up. Those who disagree with early parts of this post, please press on to the end. SPOILER ALERT: She used to play, but doesn’t anymore. Here we go.

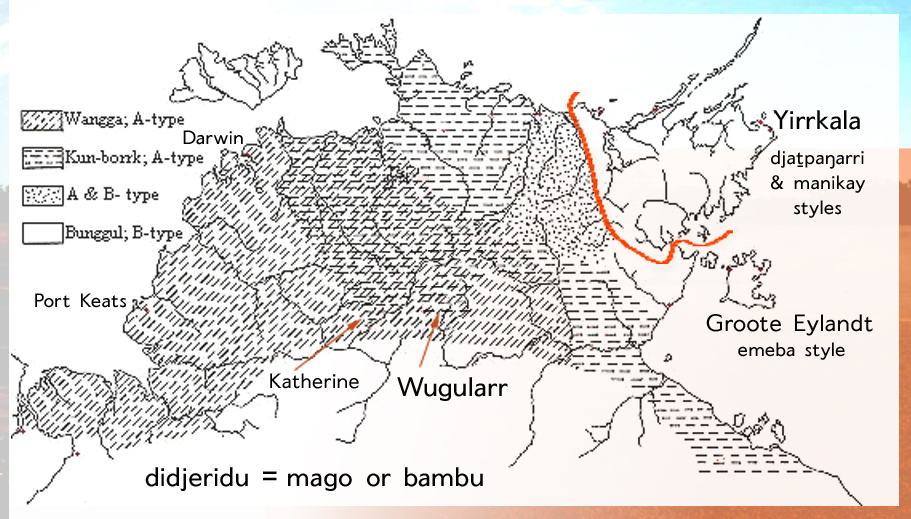

First off, the didjeridu comes from the Top End.

Period. That refers to a large area and we cannot pinpoint one origin of the instrument within it. Different Aboriginal groups across the Top End tell different stories of the didjeridu’s creation. I have no interest in judging them or choosing between them and won’t discuss academic theories on that issue here. I also won’t take time debating the larger point. Although exact borders can’t be drawn, academics and many Aboriginal People from around Australia agree that the didjeridu comes from the north of the Northern Territory and spread from there. I accept this as fact.

Stories of physical harm or sudden pregnancy coming to women who play are oft repeated outside of that area. I’ll never forget a woman who came to me in tears many years ago, telling me how she went to pick up a didjeridu in a tourist shop in New South Wales, but an Aboriginal man in the shop snatched it from her and yelled at her. It broke her heart both that she wanted to play but wasn’t allowed, and that she unintentionally offended this man.

Countless arguments about this litter social media. Non-Aboriginal women post pictures or videos of themselves playing and find themselves the target of great ire from Down Under. From both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal People, but not from traditional owners from the Top End as far as I’ve seen.

I visited a few times then lived in northeast Arnhem Land for 5 years, working with countless Yolŋu People while completing a Fulbright & M.A. project on the instrument. No one gave me a reason why Yolŋu women don’t play. It simply is not done. I only heard the cautionary story of didjeridu playing making a woman pregnant once. Banduk, who lived in Sydney for many years, referred to it as a superstition.

One Woman’s Experience in Top End Didjeridu Country

Brandi and I met in the USA in 1997 through our shared interest in the didjeridu and went to Australia for the first time in 1999. We started in Sydney, and didn’t have any issue with her as a woman player there, apart from one semi-related suggestion by an Aboriginal Person that she would be speared once we got to the Top End where the law was much stricter.

We made our way north to Katherine, where we had no trouble shopping together for instruments at stores managed by white Australians. From there, we made our way to an Aboriginal community in Top End didj country for the first time. Manyallaluk offers day tours for tourists. Local people take you for a bush walk to talk about medicinal plants and native foods. We ate kangaroo tail and drank green ant “tea.” We threw spears. We heard “Dreaming stories” of the place and had a quick go at painting on bark.

And then, out came a didjeridu for everyone to try. Everyone. It was passed around for the whole group, men and women alike. Most people of course failed to play it. I wondered what the reaction would be when it got to me, the hot shot that people in the USA thought was so good. Mostly, it was buzzkill for all our fellow tourists who had just failed at it. Our local Aboriginal hosts reacted with, “hey, that’s cool, you know how to play.” I told them that I would soon be hosting a workshop with David Blanasi back home.

Then I passed it to Brandi. She played and our male tour guides went nuts. They laughed and applauded. They called over the other men and women of the community sitting nearby.

“Hey, you’ve gotta come see this white woman who can play didjeridu! She knows Blanasi!”

Instead of bringing out the spears for punishment, the moment brought a bit of joy and wonder to the community for a minute – though admittedly, it excited the men more than the women. It seemed that somehow, in 1999, this was really the first time these men had seen a woman play didjeridu with any competence. I’m sure this didn’t instigate a cultural revolution such that we’ll go back and find that all the local women play now. I know their culture holds strong. But this cross cultural moment brought no shame, anger or warnings of impending physical harm or pregnancy. Just a pleasant surprise for all concerned.

On to Yolŋu Country

A few weeks later, we found ourselves staying with Djalu’ Gurruwiwi’s family at Gunyaŋara’ in northeast Arnhem Land. Djalu’s fame hadn’t reached today’s heights yet, but he had traveled and hosted visitors before. A woman player didn’t shock his family as it did the residents of Manyallaluk. They accepted Brandi. As a western couple, we planned to do everything together while on our trip. But she was smart enough to see that not all was right.

Both at Manyallaluk and Gunyaŋara’, Aboriginal People lead lives somewhat divided on gender lines in a way we as an “enlightened” couple from the USA didn’t. When we popped in to Manyallaluk for one day, a white woman didj player was cool. Staying at Gunyaŋara’ for a few weeks, however, was a different story. It got a bit awkward. Once Brandi suggested that we go our separate ways, with me doing men’s business like didgeridoo playing while she joined in women’s business, our relationships with the Yolŋu improved. We did as the Romans did and fit ourselves into their world view rather than insisting on bringing our own to their place.

That’s not to say yidaki is 100% men’s business. In Djalu’s family, everyone helps in the crafting process. During our first yidaki cutting trip with Djalu’, his wife Dopiya brought me a log she just chopped down, asking me to test its playability. A small, irregularly shaped mouthpiece hole sat in the middle of a thick log. With my little lips, skinny face, big nose and prior experience mostly with beeswax mouthpieces, I couldn’t fit my face on there and get a seal to try it properly. Dopiya gave up on me, took it into her own hands and blew a drone on the log for herself. Just for testing purposes since this white kid was worthless.

Brandi assisting Djalu’ in 1999.

Brandi assisting Djalu’ in 1999.

Before this trip, Brandi wanted to be a hot chick with a stick.

Few women publicly performed on didjeridu around the world. Joining those elite ranks was a sure way to get attention. The experience of the instrument’s context in Arnhem Land changed that for Brandi. It wasn’t about her anymore and she’d rather do what the women do. We visited the family a few times, then lived nearby for 5 years, immersed in life there. Brandi blew a note or two over the years, same like Dopiya testing out freshly cut instruments for herself, but she never went back to being a chick with a stick. It wasn’t appropriate for the life we lived, and it wasn’t nearly as fun as hanging with the women. As Merrkiyawuy said, Yolŋu men and women respect each other’s roles.

This is not absolutely the right answer for everyone. Djalu’s late sister (WARNING to family not to click unprepared on the following video) voices her opinion clearly. It’s up to a woman to decide for herself, but Yolŋu women will stick to their traditions.

I suppose the best thing now is to reiterate the summary I wrote for the Yidakiwuy Dhäwu.

So the best advice for non-Yolŋu women is to make your own choice for what you do on your own time, knowing that there are some Yolŋu who would encourage you to play. But be very sensitive about who you are with. If you are in Arnhem Land or in the presence of people from Arnhem Land, carefully check that no one will be upset before playing. Be aware that it may be shocking, and may inspire the laughter that women playing does in initiation ceremonies. Yolŋu women have their own business, and like to stick together and stick to their customs. You will not win any friends and begin a relationship of open sharing with Yolŋu by forcing your point of view, and will likely alienate Yolŋu women who could otherwise become friends.

As I said above, this paragraph was written to represent Yolŋu opinion, but from my own limited experience, I would apply that same view to the rest of the Top End didjeridu origins in the Northern Territory. You won’t be judged as harshly as you would by people from other parts of Australia for playing didjeridu, but you won’t make friends with local Aboriginal women that way, either.

If you just want to play the instrument and don’t plan to ever be involved with Aboriginal People,

then know that some people at its origins feel you have that choice. People like Djalu’ Gurruwiwi.

People like Western Arnhem Land mago master David Blanasi who allowed women into workshops like the one I arranged in San Diego in 1999.

But also know that like any other subject, you will run into arguments about it on the internet. You will never win that argument. Those people, if they’ve read this far, are not convinced by me right now. But I personally believe all the evidence that instrument originates from the Top End and only recently spread all over Australia. I choose to listen to traditional owners from that region. Not that 100% of them agree on this issue.

I also choose not to pick fights with people from outside that region. Please don’t insult them or intentionally cause confrontation to assert your own view of your rights. They have their own struggles in the aftermath of the invasion of their country and intentional destruction of their culture. They are proudly holding on to what they can. They deserve understanding and respect.

So. Make your choice.

Do what you gotta do. If you decide to play, know that some Aboriginal People will support your decision. Many won’t. Be respectful wherever you are, including the internet, but don’t feel you need to hide yourself, either. I wish there was an easier answer for every situation to keep everyone happy but there isn’t.

Well done, once again. Thanks for sharing your opinion and most importantly, those of the Yolgnu people.

Great article. I have often had to show respect for Native American traditions these days by not mentioning some of my own history since (a) it was very personal, (b) I am not out to prove something and (c) native people are often veey sensitive about their traditions after centuries of seeing them ripped off and over-commercialized. I will say that one medicine man i knew very well asked me to play the didj for him. He fell in love with it so I gave him that didj. Gift giving is also one of the most important native traditions in many cultures.

By the way, in that 1999 Workshop with B*****i, I wanted to give him a Native American traditional gift but didnt know how. I was “guided” to offer him a tabacco tie. He was blown away and later confided in me that Aborinal people also honor tobacco as a sacred plant!

Tobacco is indeed a good gift. It’s not native to Australia, but was brought by Macassans (from present day Sulawesi in Indonesia) who came to northern Oz on the tradewinds for hundreds of years before European settlement. It became an important trade good for northern Aboriginal People, one which could only be gotten as a gift or payment for services from an outsider.

Hi Randin,

great article, thanks for sharing 🙂

As you said, “It´s simply not done”.

From a daily life perspective, it´s a bit easier to understand, iat least that´s how i see it.

Of course, indigenous people around the world nowadays read, quite some have acces to the internet, and all that. But the background is a different story.

In a society, where knowledge was passed on from generation to generation without books, GPS and internet, it was crucial to pass on 100 % of the known information at present. To enable future generations to live off the country and care for the land as good as the present and previous generations.

To know everything that´s needed which includes of course to be able to orientate in your area.

Life-time is limited, it´s shared between learning and teaching.

Being born, finding your place in the community, learning everything you need to fully fill that place, passing on as much as possible of the knowledge to the next generation before you die.

The knowledge is passed on in songs, dance, stories and paintings, as well as in every day life experiance you can achieve by learning from an older person.

If you want to learn ALL she or he knows, you hardly will have time to develop hobbies.

OR, expressing it a bit more radical; If you do develop hobbies, you won´t learn all she or he can teach you.

Which would lead to loss of knowledge not only for you, but for the whole clan.

Example:

If you in your young age turn out to be a gifted hunter, that´s what you are busy with. Learning to read animal tracks, learning when to hunt the different animals and when better not to hunt them, where to find them, how to kill them and all that.

Later on you pass on all that knowledge – and hopefully live long enough to be able to do so.

That example most likely is representative for just any role in the clan you could have picked up.

If you can´t hunt for weeks, because you didn´t learn how to, where to and when to or not to (as you were following Yidaki lessons instead), as a consequence everyone in the clan has less to eat, or nature gets out of balance if you hunt other animals instead.

For the moment. And for the future, too. As the knowledge will stay lost unless neighbour clans share it.

So there is very few time for hobbies that require some dedication.

And if you seem to not be dedicated enough to your own business in the clan, you might be sanctioned/punished to prevent harm from the whole clan – so you don´t even think about it. Neither being a man nor being a woman.

And that background is still working today.

Would you think that this might be a valid explanation ?